Timbro Authoritarian Populism Index 2017

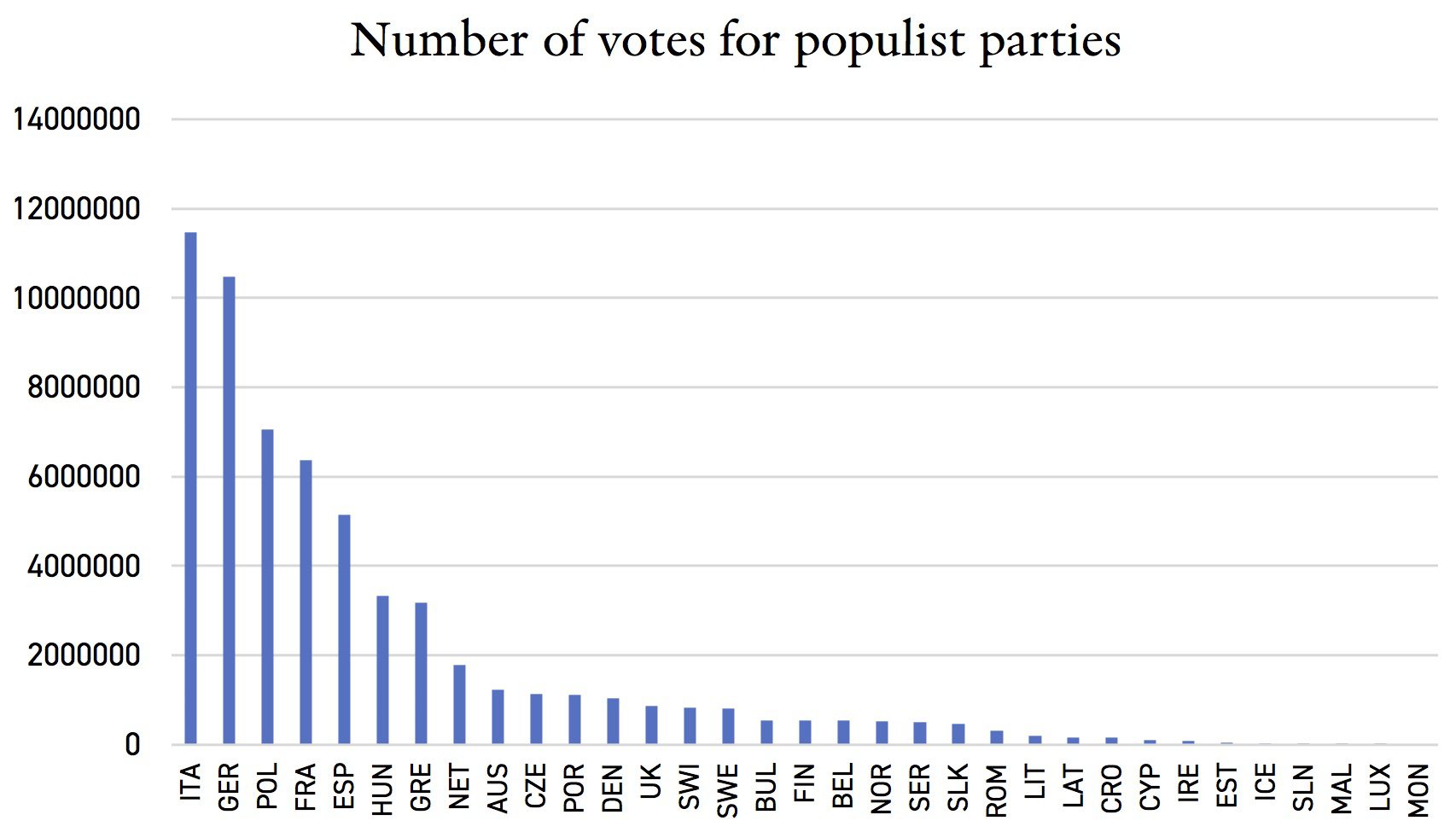

The 2017 Timbro Authoritarian Populism Index is the only Europe-wide comprehensive study that aims to shed light on whether populism poses a long-term threat to European liberal democracies. The Index explores the rise of authoritarian populism in Europe by analysing electoral data from 1980 to the summer 2017. As data show, Authoritarian-Populism has overtaken Liberalism and has now established itself as the third ideological force in European politics, behind Conservatism/Christian Democracy and Social Democracy. Hungary, Poland and Greece are the European countries where anti-establishment parties are the strongest. At the same time, nine European countries (including seven EU Member States) have populist parties in government. On average, around a fifth of the European electorate now vote for a left- or right-wing populist party. In other words, 55.8 million people voted for this parties during each European country’s latest general elections.

About Timbro Authoritarian Populism Index

Timbro Authoritarian Populism Index was first published in June 2016. Its purpose is to map the influence of populism in European politics. Currently it indicates that every third European government consists of or depends on an authoritarian populist party, and that populist parties on average attract approximately twenty percent of European voters.

Since the first report, the index has been translated into several languages and referred to by scholars and media in a large number of countries. An update of the state of populism in Europe is therefore provided in a second edition: Timbro Authoritarian Populism Index 2017.

The updated index maps the status of populist parties in all parliamentary elections in Europe from 1980 to the end of 2017. Its focus, however, is especially directed at actual trends over the last year —a more extensive background is found in the report of 2016.

The 2017 index adds to existing surveys in three different ways. First, it maps populism along the entire political spectrum. Conventionally, mapping political populism aims exclusively at right-wing populism. However, if the purpose is to defend the fundamental values of Liberal Democracies and institutions it calls for a broader assessment, ranging from left to right.

Secondly, the index focuses on trends, not snapshots. The fact that all political parties in every European democracy are mapped from 1980 to the present, provides context that rarely is found in media’s day-to-day reporting, where the impact of individual parties’ accomplishments or failures tend to be exaggerated.

Thirdly, the index shows that the populist threat contains a multitude of agents and dimensions that hardly fit the traditional left-right narrative. A problem in scholarly literature has long been the confusion of anti-Democratic parties with anti-Liberal parties. An exclusive focus on the rhetoric of populist parties has a tendency to underrate the authoritarian aspects central to ideologies and practices of populist parties.

It is true that all political parties to some degree make use of populist rhetoric. In addition, populism in itself is not always a threat to the democratic process. Hence, we cover only parties where populism in and of itself has become an ideological property. This intellectual tradition is recognizable in its opposition to the separation of governing powers; its idea of a homogeneous people with common interests; its relentless attacks on “the elite”, &c. It also incorporates, for practical purposes, an authoritarian outlook that threatens the values and principles that have been at the center of European democracy since the Second World War.

Executive summary

- Authoritarian populism has surpassed Liberalism to become the third most dominant ideology in European politics.

- Populist parties continue to achieve electoral success at record-breaking levels, but have not gained further support since 2015.

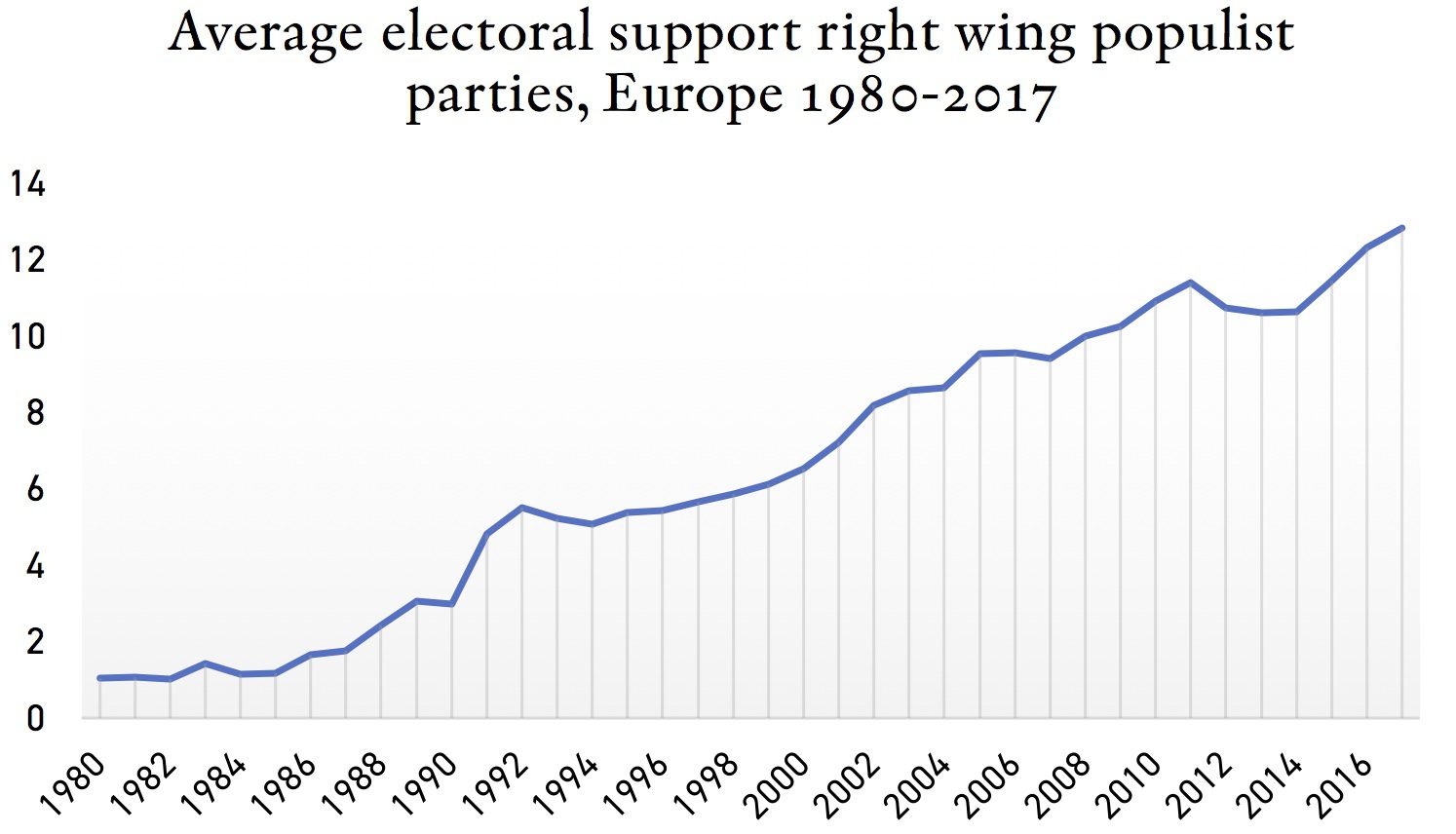

- Right-wing populism is twice the size of left-wing populism, but while right-wing populism has stagnated, left-wing populism has doubled since 2010.

- Hungary, Poland, and Greece remain top-three in support to populist parties, while the weakest support is found in Montenegro, Malta, and Iceland.

- Anti-democratic parties are still marginalized, but show minor gains during the last year.

- Today, ten European governments contain authoritarian, populist parties. This is more than ever before.

Introduction

During the last 18 months, two separate media narratives have been trading places. In 2016, almost every election was reported as a temporary halt all over the West on the road to victory for populist parties. This storyline emerged already in the spring of 2014, during the campaign leading up to the election of the European Parliament. It grew in strength in the wake of Brexit and the British referendum of June 2016, and following Donald Trump’s successful run in November of 2016, many pundits predicted a corresponding success for Geert Wilders and Marine Le Pen.

This did not come true. Right-wing populists in France and the Netherlands underperformed, and UKIP was more or less eradicated in Britain’s sudden election. Thus, the dramaturgy quickly changed from one of unstoppable populism to setting up its forthcoming demise. Suddenly pundits started talking about ‘peak populism’.

Looking back, the election in the Netherlands can be viewed as a watershed. International reporting assumed victory for Wilders even during the last days before the election, although polls at that time strongly pointed to weakening support for PPV. Hence, media after the election focused almost exclusively on Wilder’s debacle despite the fact that his party actually gained three percentage points compared to the previous election.

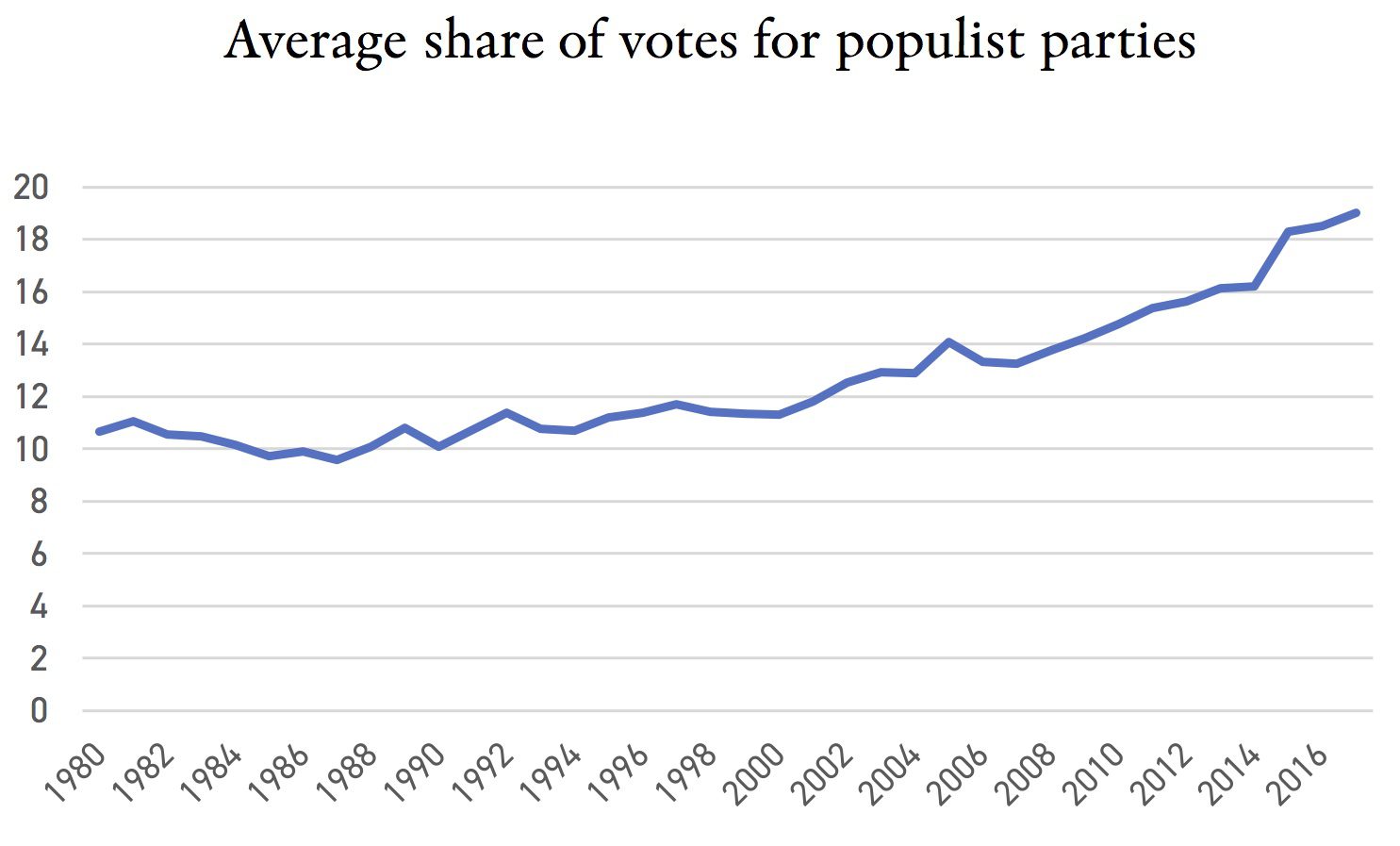

It is obviously impossible to know for a fact that populism has reached a temporary peak. It must be stressed, however, that populism still captures record-high levels. During 2017 populist parties have achieved success in five elections while under-performing in three — and in two elections populist support has remained on previous levels. The totality of support for populist parties in Europe is higher than ever before.

Today, authoritarian populism has established itself as the third ideological tide in European politics, next to Conservatism and Social Democracy. In the previous election to date in Europe more than one voter in five—22.7 percentage—voted for a populist party. These parties differ in many ways, but are united by two distinctive properties: First, they position “the people” against “the elite”, and portray themselves as true representatives of a homogeneous people abandoned by this corrupt and conspiring elite (political, economical, cultural); secondly, they partly or entirely reject the long-standing foundation of Western Liberal democracies, i.e. separation of powers, transparency, and individualism.

On average, these parties earn 19 percentage (The difference of more than three percentage points between, on the one hand, the number of people voting for these parties and, on the other, their average result, follows from the fact that populist parties are stronger in more populous countries.) Five in six of these votes—approximately fifteen percent—go to democratic but anti-liberal parties, while the sixth vote (about three percentage units of the totality) supports anti-democratic populist parties. This should be compared to the all-in-all twelve percent for parties with ‘liberal’ as their primary designation.

At the end of 2017, ten governments in Europe include one or more authoritarian populist parties. This is a higher number than any other year. Two parties govern from a majority position—Fidesz in Hungary and Law and Justice (PiS) in Poland, while the majority are minor coalition partners. The only left-wing party is Syriza in Greece, while the rest are right-wing populist parties.

In last year’s report, our claim was that the populist success constituted, “… the largest change in the European political landscape since, at least, the fall of Communism” and that it in Western Europe was, “… the largest change since the breakthrough of Democracy.” This analysis holds fast. It is grounded partly in the strong impact of these new parties, and partly in the distribution of the non-Liberal—although democratic—ideas they embrace.

What is populism?

Any concept that reaches a certain level of popularity is at risk of becoming worn-out, used in so many different, mutually inconsistent, ways, that it no longer serves a meaningful, analytical tool. The concept of populism is of this kind. Is it even possible to speak of populist parties when ‘populism’ constantly is used as an invective?

Yet, it would be a shame if populism were reduced to a punishment rod for those who wish only to invalidate opponents. The concept delves below the political surface. In everyday usage, ‘populism’ almost always refers to the less than admirable practices of politics: vulgar rhetoric, weak or nonexistent claims of political consistency, opportunism. None of these are unique to the parties we deem populist. On the contrary, populism as a communicative method exists within all parties. Message, and at times positions, are tailored to what is perceived as voter-friendly. Complexities are over-simplified, conflicting goals dismissed. If populism is understood like this it necessarily becomes a matter of degrees—political parties and their representatives are more or less populist.

In essence, however, populism is not about communication, but ideology. It is emphatically not an ideology that presents a holistic view on society and politics, but it does make claims comparable to Liberalism or Socialism, and contains assertions on the same level of abstraction as these standard ideologies.

The most basic populist assertion is that the conflict between elite and people supersedes all other conflicts. According to some—mainly left-wing—populist parties, the left/right spectrum is still a valid dimension, while others regard this conflict as a mere charade created to convolute the interests of the elite in its control over the people. Regardless, socio-economic divides are of secondary importance to all populists.

In contrast to political style, this idea-based content exclusively separates populist parties. Other parties don’t assume a world-view where a whole-sale elite is in opposition to the people. It is an exclusively populist idea in the sense that it is shared by all populist parties while rejected by all non-populist parties.

Populism and the establishment

Political scientist Amir Abedis (2004) prefers ‘anti-establishment’ over ‘populism’. He sets up three criteria for a party to be categorized as anti-establishment. It will,

- … challenge the status quo in terms of major policy issues and political system issues.

- … perceive itself as a challenger to the political establishment.

- … assert a fundamental divide between the political establishment and the people.

Regardless of whether they are referred to as populist parties or anti-establishment parties, the core will consist of opposition to elite and establishment. At their worse, representatives of established parties dismiss all populist criticism as irrelevant, erroneous, or conspiratorial. However, even when this is true for a large portion of populist disapproval it still falls short of a full description.

Since the first decades following the Second World War, European politics have been characterized by a widespread middle ground. Social Democrats, Liberals, Christian Democrats, and Conservatives in Scandinavia and Northwest Europe have shared a remarkably similar view on representative democracy. It has combined basic respect for the conditions of majority rule with a gradual expansion of individual rights. These rights have been constitutionally safe-guarded or protected by international agreements beyond the reach of fleeting parliamentary majorities. There has also been strong support for independent courts, independent media, and mechanisms defending minorities from majority oppression. During the 1980’s, parties emerging from the environmentalist movement championed the same values, as did many reformed socialist parties after 1990. As a consequence of these shared views, political rhetoric and aesthetics—as opposed to political content—have seldom changed, even when political power has shifted between parties or blocs.

Europe’s identity and self-perception have come to build upon these liberal, democratic institutions and values as they have been transferred to shared institutions—EU, European Council, OSSE—and paved the way for fledgling democracies from Southern and Eastern Europe to join the European project.

This development has also created a largely shared view on important aspects of the political content. Going back decades, almost every established party in Europe is a supporter of the European Union, and most have basically a positive attitude to economic and cultural globalization.

Today, there are severe challenges to this state of affairs. A few years ago, BBC described Law and Order and Fidesz, the governing parties in Poland and Hungary and currently Europe´s most successful populist parties, as challengers to, “… the European consensus and politics as usual.”

Hence, when supporters of populist parties are portrayed as protesters rather than opinionated voters, it renders an image both true and false. True, since protest in itself in large motivates these voters. False, since protests not necessarily conflicts with a comprehensive political outlook. Hence, the following overlapping logic:

- The fundamental populist idea is the prevalence of a corrupt elite that makes up the establishment.

- Hence, to simply join in this protest will imply subscription to the ideological starting point of populism.

Populism and democracy

The populist relation to democracy is complex. In many interpretations populism comes across as a singularly negative phenomenon—even a threat to democracy. Others hold that populism is an important part of democracy and expresses a crucial tension between elite and electorate.

Political scientist Takis S. Pappas has suggested (2016) ‘democratic non-liberalism’ as a definition of contemporary populism: It recognizes the majority’s right to make decisions, but excludes liberal constraints on political power. This allows, as pointed out by political scientist Cas Mudde (2007), populism to become an alternative to non-democratic liberalism. At its best populism can function as a remedial for a political elite that fails to respect the rules of democracy.

European parliaments have always contained parties that reject the very democratic system within which they function. There is, however, an essential, qualitative differences between, on the one hand, parties that explicitly reject democracy and its form of governing, and, on the other, parties that from within the system want to compromise the rules of democracy. It follows that it is difficult to draw a demarcation line between authoritarian populism and the left-wing (Stalinism, Trotskyism, Maoism, Leninism) or right-wing (fascism, neo-nazism) totalitarian parties that emerged after the Second World War.

Fig. 1: A schematic overlook on possible versions of populist parties with respect to their view on democracy v. liberal principles.

| Democratic | Anti-democratic | |

| Liberal | Anti-corruption | – |

| Anti-liberal | Authoritarian populism | Left and right wing extremism |

The upper, left corner represent a small number of parties, mainly stemming from Eastern Europe. They are adamantly anti-establishment, use unforgiving rhetoric, but still do not in essence depart from liberal principles. Hence, they are not included in this study. It is true that they are populist, but since “the European consensus” often is represented by the anti-establishment parties rather than the more or less corrupt elites, it would be erroneous to include them in an index where the primary purpose is to map a threat to liberal democracy.

The upper right corner is empty. Libertarian or anarcho-liberal groups that reject democracy belong here, but such factions scarcely form political parties.

In the lower right corner we find parties that are both anti-liberal and anti-democratic. Historically, this category includes the successful challenge against Western democracies during the Cold War era, i.e. communism and fascism. Today, it is primarily represented by right-wing extremists combining ethnic nationalism with populism—Hungarian Jobbik is a prototypical example—but it also includes remnants of left-wing extremists (Trotskyism, Leninism, &c) that dismiss the entire political elite and claim to stand for the people.

For our purposes the lower left corner is especially interesting. It captures populist parties that are deemed democratic though they explicitly reject liberal principles. I have labeled these parties ‘authoritarian populists.’

Authoritarian Populism

Authoritarian populism is an analytical category, i.e., it is a product of armchair philosophizing. It corresponds largely to two existing party lineages: right-wing populism and left-wing populism. It must be underscored that this category contains a great variety of parties. It does not constitute a family of parties and the selection reflects a minimum of similarities. Ideological differences between parties in this category are often substantial, not only within sub-categories, and many are each others’ sworn enemies.

Differences between right-wing populist parties abound as seen in the endless struggle to form a cohesive bloc in the European Parliament to the right of EEP (Conservative European People’s Party.) Partly, the difficulties derive from personal conflicts, but primarily they stem from essential dissimilarities. After all, these parties trace their history back to as widely different origins as Nazism or Liberalism. Some are radical nationalists, others rely on pure opportunism, while yet others can be found on the slippery slope from xenophobia to blatant racism.

In a similar way, left-wing populism includes parties with their roots in Marxism-Leninism as well as parties grown out of the peace movement of the 1970’s; theoretical socialists next to movement representatives.

Nonetheless, despite these tensions and sometimes outright contradictions, the unifying label of authoritarian populism is justified by at least three properties.

1. People v. Elite

Populist parties think of and portray themselves as the true representatives of the people standing up to the elite. Margaret Canovan (1999) has made the observation that populist movements both on the left and the right take for granted that there actually exists “one people” and that it is excluded from power, “… by corrupt politicians and an unrepresentative elite.” This primary characteristic of populism is rarely found among traditional parties.

An immediate consequence of the claim to represent “the people”, rather than ideas, is that traditional dividing lines and conflicts of objectives are erased. Lega Nord’s former chairman, Umberto Bossi, tellingly described his party as, “libertarian, but also socialist”, while FPÖ’s Norbert Hofer, a hair’s width from becoming the president of Austria in 2016, describes his party as, “… [a] center-right party with a degree of social responsibility.” In Sweden, populist party Sverigedemokraterna has systematically portrayed itself as positioned outside the left-right conflict, which allows it to cherry-pick conflicting policies from left to right.

2. Democracy without speed-bumps

Secondly, authoritarian populism lacks interest in and even patience with constitutional rule of law. Anton Pelinka (2013, p. 3) defines populism as, “… a general protest against the checks and balances introduced to prevent ‘the people’s direct rule’”, and political scientist Tritsjke Akkerman (2005) concludes that populist parties are, “activists with respect to the law.”

A natural corrective of populists’ lack of trust in the political elite is their general demand for increased direct democracy and specific support of various referenda: on EU; on immigration; on minority rights, &c. Denmark’s Dansk Folkeparti and Norway’s Fremskrittspartiet both argue that it ought to be possible for citizens to demand a binding referendum on any issue; in Sweden, Sverigedemokraterna advocates a referendum on immigration.

The previously successful Polish populist party Samoobrona’s chairman, Andrzej Lepper, has formulated this view on democracy sententiously: “If the law works against people and generally accepted notions of legality then it isn’t law. The only thing to do is to break it for the sake of the majority” (in Mudde, 2007, p. 154.)

Hence, populists prefer fewer speed bumps in the democratic process in order for temporary majorities to legislate and enforce new laws. Mechanisms to slow down the procedure are regarded as stumble blocks for the majority. Collectively, the one people takes priority over individuals or minority groups. Right wing populists, as soon they reach power, says Cas Mudde, practice the ideal of, “… an extreme form of majoritarian democracy, in which minority rights can exist only as long as they have majority support” (Mudde, 2007, p. 156). This also means that courts shouldn’t be allowed to veto legislation, which explains the oft-seen conflicts between authoritarian populists in power and constitutional courts. In the early 2000’s, FPÖ enforced laws at such speed that several were repealed by the Supreme Court after the fact and on purely procedural grounds. Also in Hungary and Poland populist governments have rapidly changed or commenced to change the rules of the game. Among the propositions that have met with especially harsh criticism from the international community is the limitation of the role of the constitutional courts.

In this, at least, right-wing populism overlap the ideas of nationalism: The nation is the people thus a majority of the people shall rule the nation. Minority rights, then, constitute an obvious threat to this populist view on democracy. As Cas Mudde says: “… all populist radical right parties are nationalist, but not all nationalist parties are radical right populist.” In the new left-wing populism a new phenomenon is emerging compared to the traditional left. The left used to refer to defined categories as ‘class’, ‘worker’, ‘capitalist’, &c. Segments of the population were in a permanent conflict of interests with other segments of the people (class v. class, workers v. capitalists.) Contemporary left-wing populism, however, has an all-encompassing concept of the people in a way that more resembles today’s right-wing populism than yesteryear’s left (Zaslove, 2008).

3. A state with stronger muscles.

A third similarity is the quest for a more powerful state. Jobbik’s campaign platform says that the party strives towards a, “potent, active, and capable state,” (Lerulf, 2012, p. 29). This is representative for virtually all parties in the category of authoritarian populism as well as in the category of left-wing and right-wing extremism. The state is supposed to assume more responsibility, be a general solver of various problems, and the instrument for social and societal change.

There are of course different views on how to use the power of the state. All parties in this index contest EU and almost all are opponents to NATO. They are through-and-through hostile to globalization and generally also to free trade. They do, however, often show an affinity for Russia under Putin. Voter patterns in the European Parliament present a quick introduction to the frequency with which left-wing and right-wing populists find common ground despite their ideological differences.

Further, right-wing populists understandably propose additional resources to the police and armed forces. Left-wing populists (but also a considerable number of right-wing populists, like Fidesz and Front National) hold an authoritarian view on the free market and propose socialization of banks and large corporations. Right-wing populists typically, but not always, advocate a traditional view on family, nation, and religion. Left-wing populists in many countries instead argue for stronger rights for homosexuals and ethnic minorities. The latter, though, is true also for i.e. right-wing populists in the Netherlands.

Methodology

This report is an effort to present a comprehensive overlook of the growth of populism in European politics and includes all European consolidated democracies: thirty-three countries including the twenty-eight members of EU plus Iceland, Norway, Switzerland, Serbia, and Montenegro. A further criteria for participation is to be categorized as a “free” society by Freedom House, an American, governmental-funded NGO.

Non-democracies are excluded, since there is no real point in comparing countries where democratic rights systematically are being limited or violated to consolidated democracies. The same decision has been made for semi-authoritarian countries with regular but only somewhat free elections: Macedonia, Albania, Bosnia-Hercegovina, and Moldova. Here, the supply of alternatives to authoritarian populism is too scarce for any meaningful comparison.

The survey begins with 1980, since the overwhelming majority of today’s populist parties emerged during the 1980’s and 1990’. Most post-communist countries enter the survey in 1990; Serbia in 2000; and Croatia in 2001.

Results are included for every partiy in all elections to national parliaments. Presidential elections, elections to the European Parliament, and regional or local elections are excluded.

To make a selection among parties is not strict science. It presupposes qualitative assumptions of elements that are in constant flux. A further challenge is that parties often will be labeled in stark contrast to their self-image. The goal of the categorization is to reflect the ideologies of the parties, and few parties calls themselves populist and even fewer brag about their authoritarian streak. It is also, given the scope of the material, not possible to scrutinize each and every party. Also, I don’t claim that the categorization provides any original observations—rather the opposite. To the extent that it has been possible I have followed typical, existing categorizations. Thus, I have used a number of different sources: scholarly literature on the European party system focusing in general on populist parties as well as particular parties; ideological labels from reputable internet sources, such as www.partisandelections.eu and Wikipedia; and the expert study Chapel Hill Expert Survey (CHES), a quantitative summary of where parties belong on the left-to-right spectrum, combined with additional dimensions that serve to identify right-wing populists (but not left-wing populists) using, for instance, views on minority rights, immigration, and multiculturalism.

In general, it is not as difficult to categorize political parties as one might expect. Despite some disagreement on labels, there is a rather wide consensus on where parties fit. When in doubt, I have tried to judge the very core of a party’s ideology using both secondary and primary sources (such as official party platforms).

It should be stressed that authoritarian populism isn’t the only characteristic of the parties in the populism category. To the contrary, it is not unusual that populist parties include classical liberal aspects next to authoritarian positions. This is true for both right-wing and left-wing parties. Several right-wing populist parties—like Norway’s Fremskrittspartiet—take a free-market position on economic issues, even if, as Cas Mudde (2007) has shown, it is a myth that neo-liberalism has been of any significance to right-wing populism. Similarly, many left-wing populist parties represent a liberal view on social issues and partake in organized collaborations with anti-authoritarian socialist or green parties.

Conversely, there exist authoritarian aspects among established parties. It is impossible to draw distinct lines between populist and established parties. Paramount for this study is the role populist attitudes are given within the parties, not the prevalence of these attitudes..

A further difficulty is that many parties are in flux. This is especially true for a number of parties previously described as right-wing extremists, which during the last decade have moved away from extremism. To what degree they have actually succeeded is a question where independent commentators seldom find common ground—Front National and Sverigedemokraterna are typical examples. Austrian FPÖ is included in the study starting 1986, when Jörg Haider was appointed chairman and made anti-immigration a central part of the party platform. Hungarian Fidesz is included from 2002, when the formerly liberal party tipped over into the category of authoritarian populist parties.

Election results have been used to measure the demand for authoritarian populism. In total, 223 parties with at least 0.1 percentage in any election in any of the thirty-three countries since 1980 are included in each respective category. A European mean value based on the previous election in each country is provided in order to give a easy-to-read overview of year-to-year changes. Thus, the Swedish election of 2014 provides the basis for the Swedish average also in 2015, 2016, and 2017. In other words, the index answers the question of how many voters picked an authoritarian populist party at the turn of the year of the last election. Thus the result will not depend on whether a certain country had an election in a given year, nor on the number of countries having an election in a given year.

Two different indicators have been used to measure weight. First, the absolute number of seats in the parliament. The index shows how many seats each party has held each year in each respective category. —obviously, this measure includes only those parties that have entered the parliament. Parties such as Front National and United Kingdom Independence Party have had relatively strong performances measured in share of total votes, but as a consequence of the election systems in France and Great Britain this has been only marginally reflected in parliamentary presence. The second indicator to measure weight is participation in executive government.

In addition to compiling election results and parliament seats (a total of 119 parties have at any time won at least one seat), I have classified parties as “left” or “right”, and “authoritarian” or “totalitarian.” Left-right depends first and foremost on the classification provided by the parties themselves; when this has been problematic to apply I have used the most prevalent labels in secondary literature; in some especially difficult cases the label has been decided by the party’s choice of partner. These cases, however, have been few enough to not affect the aggregated result.

The division between “authoritarian” or “totalitarian” depends on the specific view on the concept of democracy. Only explicitly anti-democratic parties have been categorized as anti-democratic. Parties embracing nazism, fascism, communism, trotskyism, maoism, &c, it has been regarded totalitarian. Authoritarian parties are anti-liberal, but still democratic.

Timbro Authoritarian Populism Index 2017

1. Continued record high levels. Too early to speak of peak populism.

During 2017 there have been elections to parliament in ten countries. Populist parties have made gains in The Netherlands, France, Germany, Austria. In Great Britain, Bulgaria, and Czechia voter support has weakened. In Malta and Norway, the election resulted more or less in status quo. In total, populist support has continued to grow. Average support is at 19 percent.

Fig. 2: Average voter support for populist parties 1980-2017.

The index shows the average support for all parties in Timbro Authoritarian Populism Index. The number for each year is based on the election result of the last election in each country.

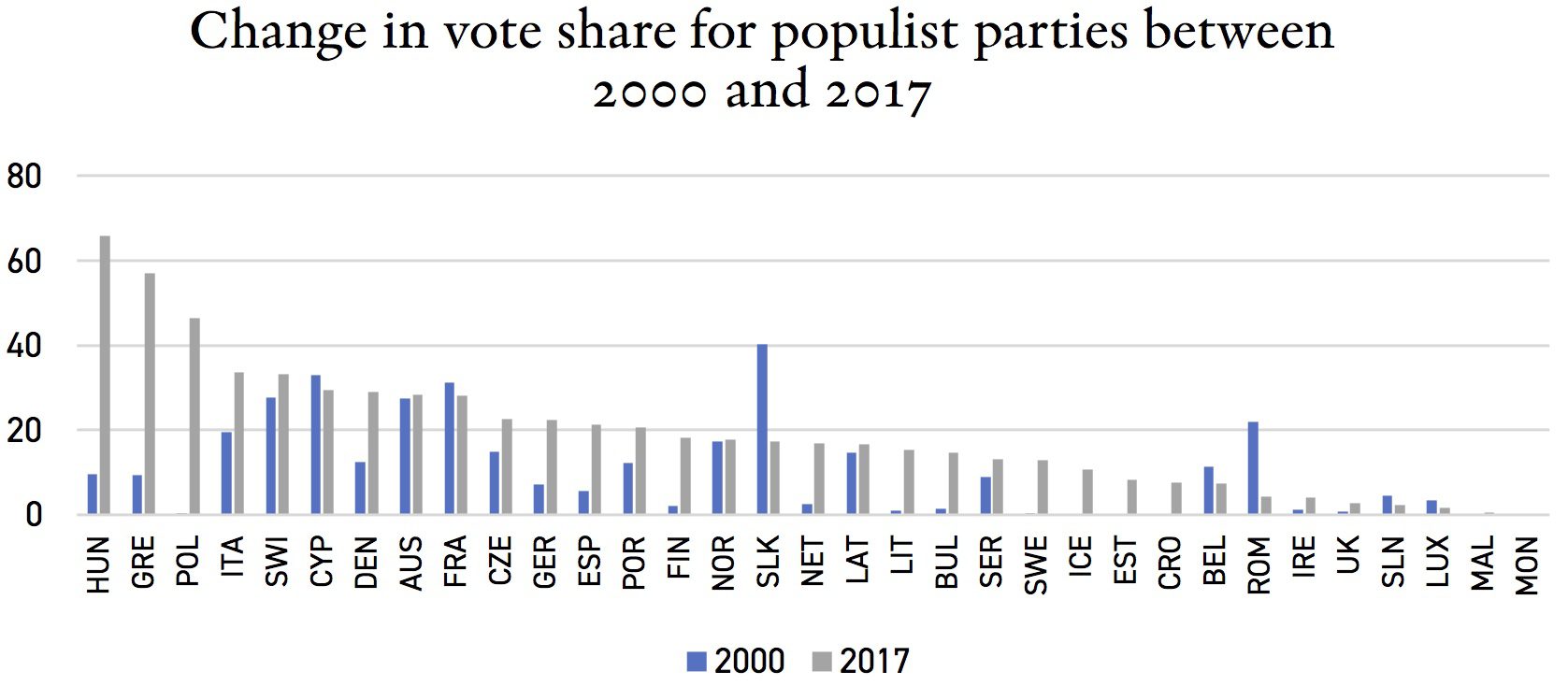

Hungary, Greece, and Poland are the three countries where support for authoritarian populist parties is the strongest. In Hungary and Greece more than half of the electorate cast its vote for populists, and all three countries are governed by populist parties. Hungary has been governed by Fidesz since 2010; in Poland PiS has been the sole governing party since 2015; and in Greece right-wing populist Anel governs in coalition with Syriza.

The French parliamentary election, while a great disappointment to National Front, still led to in total the eight strongest support in Europe for populist parties. Moreover, in the one month earlier presidential election, candidates of populist parties garnered almost half the vote.

Fig. 3: Changes in voter support for populist parties 2000-2017.

Fig. 3 indicates that the trend is the same all over Europe. Only in Slovakia and Romania do populist parties have significantly weaker support today compared to 2000. During the same period, populist voter support has grown considerably in seventeen countries.

It is noticeable that the support for populist parties is weakest in some of the least populous countries: Iceland, Malta, Montenegro, Luxemburg, and Slovenia. Hence the index actually underestimates the real share of populist voters. Populist parties won 18.4 percent of the vote, while 21.4 percent of European voters cast their vote for them.

Fig. 4: Total number of votes for populist parties per country.

2. Right-wing populism: No signs of stagnation

Right-wing populism and left-wing populism follow separate trajectories. Right-wing populist parties in the early 1980’s was a marginalized phenomenon. Only one out of a hundred votes were cast for a fascist or right-wing populist party. Beginning in the second half of the 1980’s, however, the support has seen a very consistent growth. The average for 2017—12.8 percent—is the second highest ever. At two times—mid-90’s and early 2010’s—there have been tendencies towards stagnation, but in a longer perspective the curve continues to bend upwards.

Fig. 5: Voter support for right-wing populist parties.

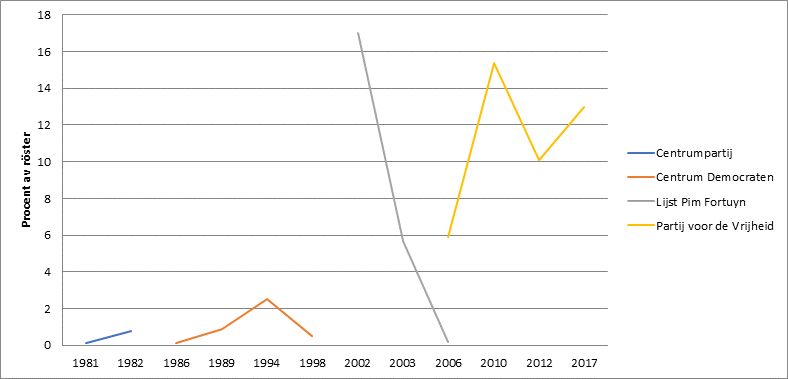

The Netherlands is a telling example. Four right-wing populist parties, all with immigration as its defining issue, have succeeded each other since the 1980’s. Centrumpartij and Centrum Democraaten had a very modest success in the 1980’s. List Pim Fortuyn was a sensation 2002, but soon fell apart. Simultaneously, Geert Wilders founded his Frihetsparti, which today is the right-wing populist party with the longest presence in the parliament, even if it never has exceeded LPF:s record share of the vote from 2002.

Fig. 6: Election results for anti-immigration parties in the Netherlands 1981-2017.

Right-wing populist parties in Great Britain have lost support during 2016-17, when UKIP dropped from 12.6 percent in 2015 to 1.8 percent in 2017; and in Bulgaria. Here several right-wing radical parties in the election of 2017 joined forces with right-wing extremist Ataka and formed an alliance, resulting in a total of roughly five percent less than what the individual parties combined in the election of 2014.

The index does, however, show increases in the Netherlands, France, Germany, Austria and Iceland.

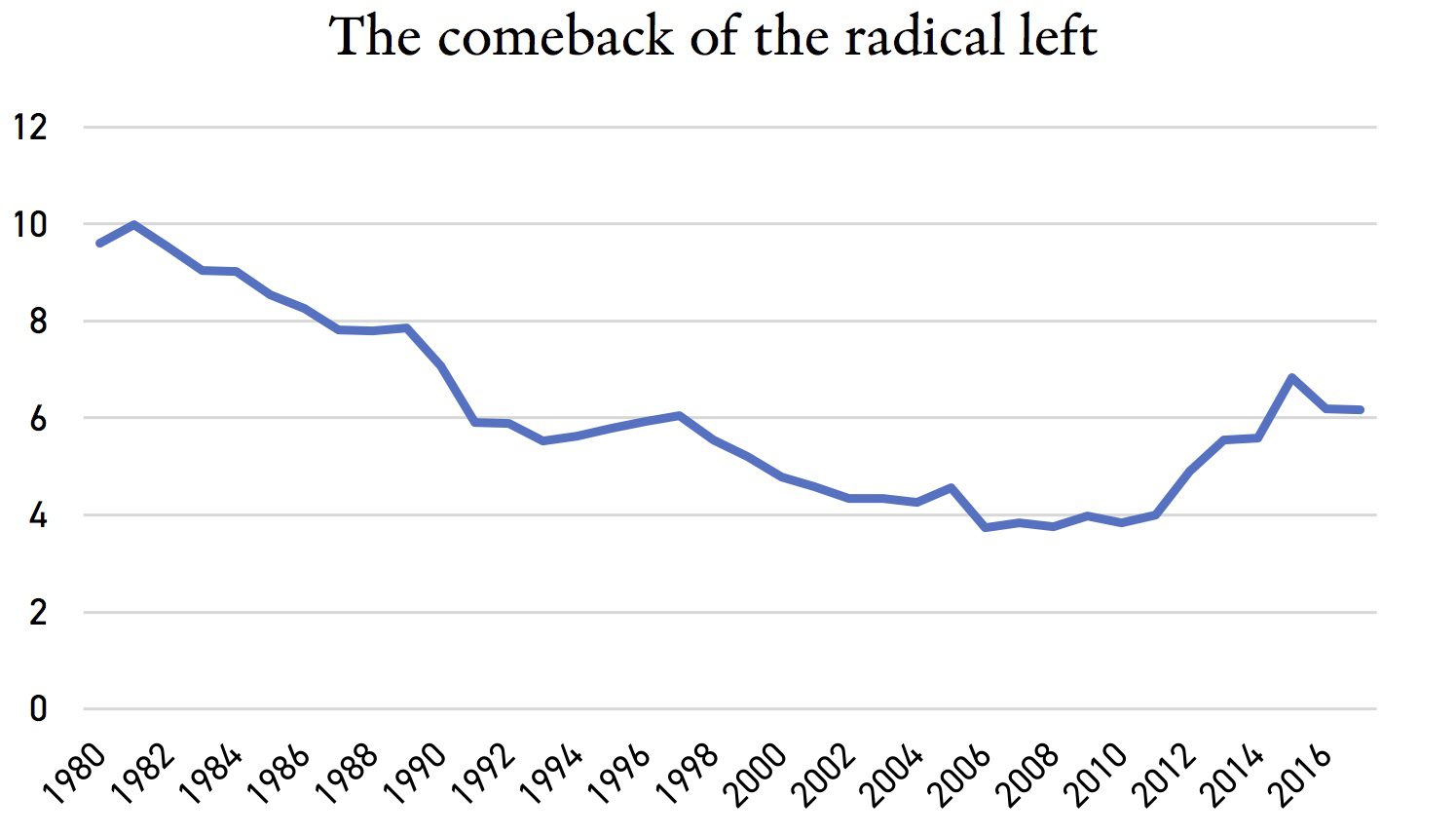

3. Left-wing populism: Has the increase flattened out?

Support for left-wing populist parties flattened out during the first half of the 1990’s, after which it continued to drop to reach its lowest level in 2006 at 3.7 percent. It was only in a handful of countries in South and Central Europe that left-wing authoritarian parties garnered any voter support worth mentioning. However, over the last five years support for left-wing populist parties has almost doubled. The increase is primarily driven by exceptional success for left-wing populists in Greece, Italy, and Spain, but the radical left has achieved gains also in countries such as Denmark, Belgium, Ireland, Romania, and Croatia.

Fig. 7: Voter support for left-wing populist parties.

During the last twelve months the support has changed significantly only in two countries—in France, where left-wing populism almost doubled its support; and in the Czech Republic, where it dropped drastically.

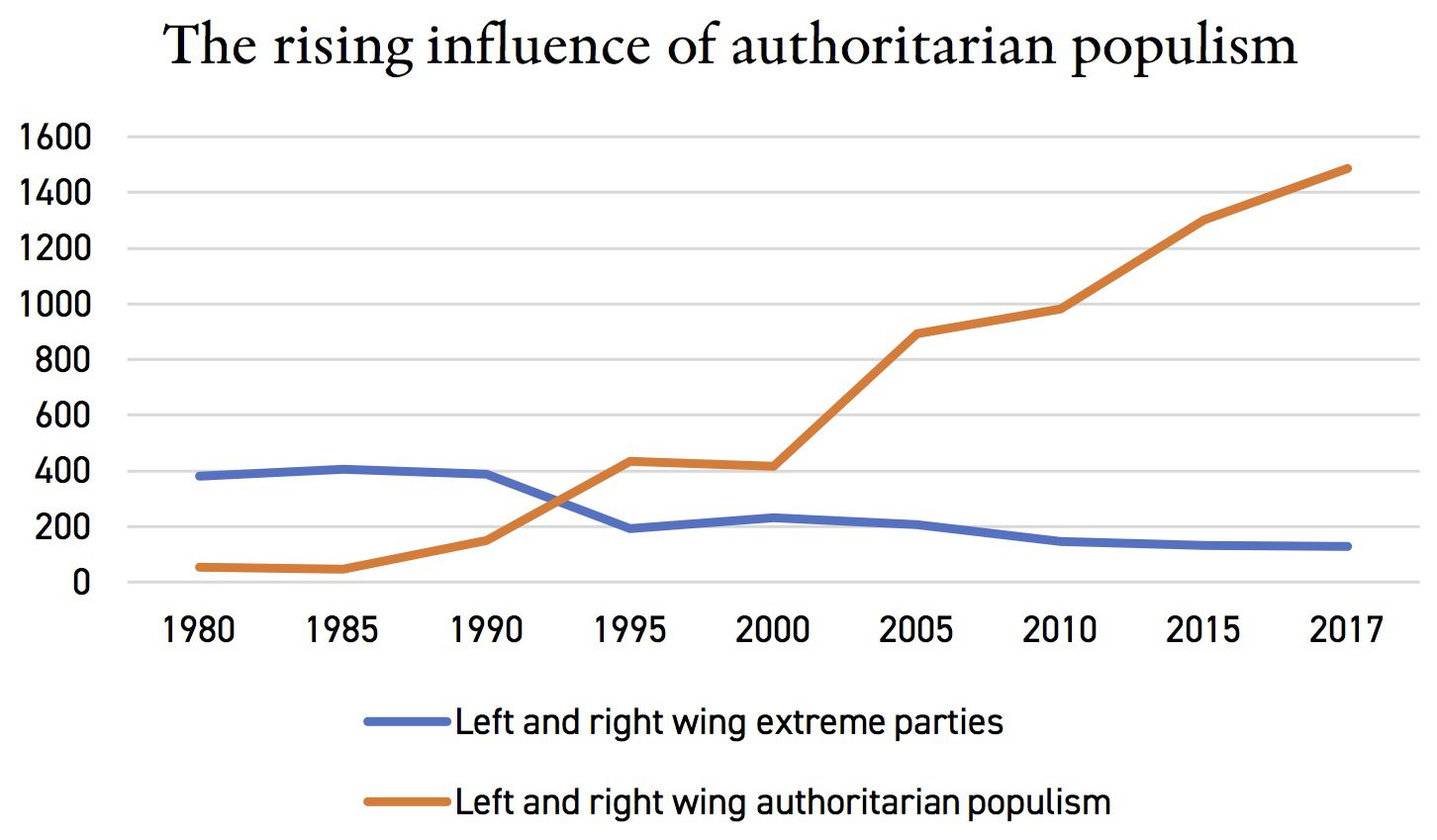

4. Stronger influence than ever before

There are a total of 7,843 seats in the national parliaments of the 33 countries included in this study. Out of these, 1,486 have been categorized as populist and pro-democracy, while 129 have been categorized as anti-democracy (“left-wing” or “right-wing” extremists). This equals 18.9 and 1.6 percent respectively, which means that more than one seat in five today is held by representatives of non-liberal and/or anti-democratic parties.

Fig. 8: Number of seats in European parliaments held by democratic or anti-democratic populist parties, 1980-2017.

Obviously, these 1,615 members of parliaments from authoritarian or extremist parties wield political power through their very presence. They influence the outcome of decisions when they cast their votes; they occupy platforms from which they can communicate their message, &c.

For some, this is where it ends. Many of the most radical parties are still isolated in their parliaments: other parties refuse to collaborate with them; informal mechanism develop in order to limit their influence; they meet with active resistance from the establishment.

The majority of these parties, however, function as regular, parliamentary party caucuses. They negotiate with other parties; they form more or less far-reaching and more or less long-lasting alliances. About a dozen, are included in or positioned very close to the executive power.

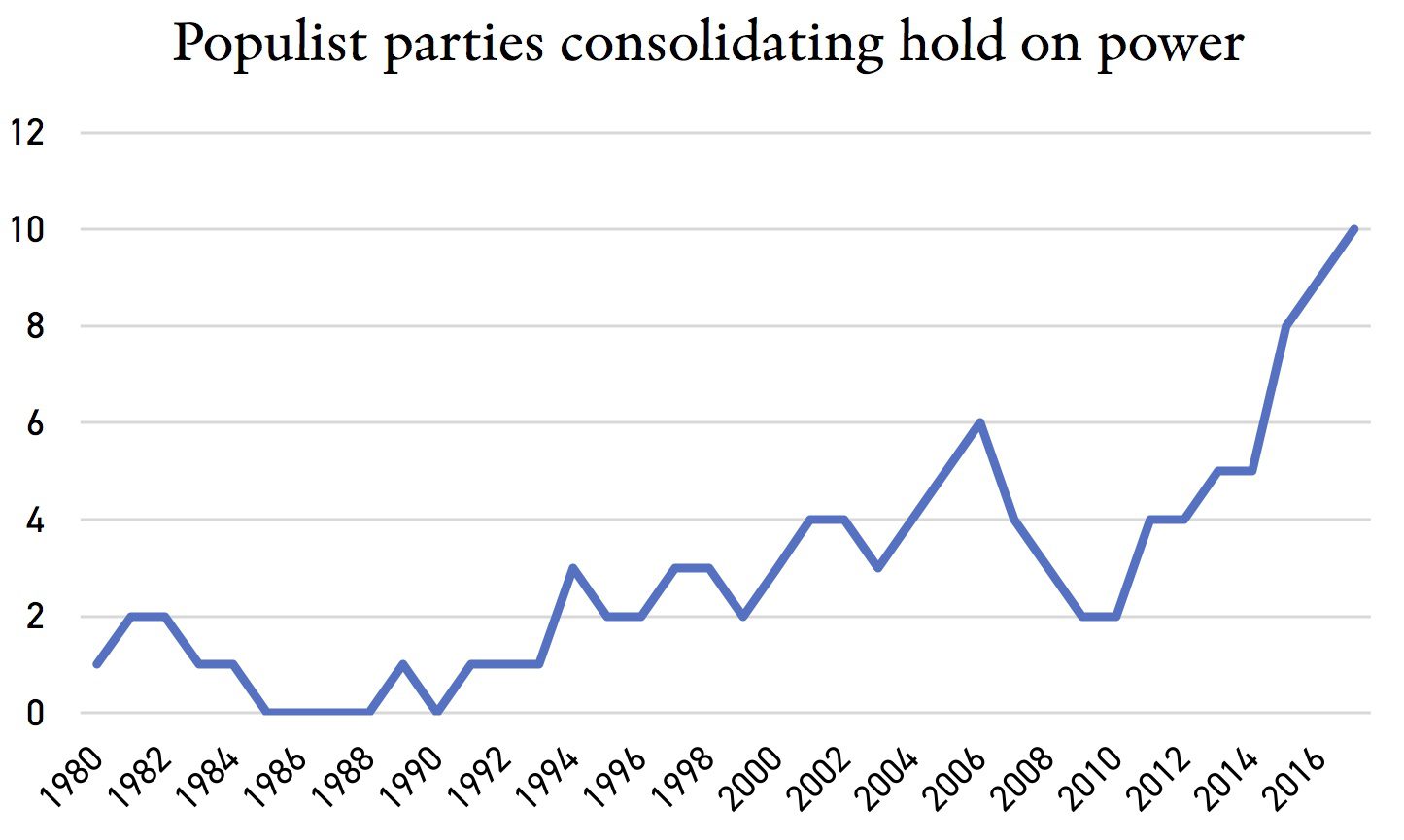

At the time of this report there are authoritarian parties in government in ten European countries: Hungary, Poland, Greece, Norway, Finland, Latvia, Bulgaria, Slovakia, Switzerland, and, following the agreements between the ÖVP and FPÖ, in Austria. During the last year the Norwegian Progress Party was re-elected, while the the three right-wing populist parties Ataka, NFSB, and VMRO (forming a technical election alliance) entered the government after the elections. In Finland the right-wing populist Sannfinländarna has been replaced by a splinter group that goes by the name Blå framtid (Blue Future), made up out of Sannfinländarna’s previous cabinet members.

Fig. 9: Number of European governments that include populist parties, 1980-2017.

What used to be an aberration has become a state of normalcy. During the 1980’s authoritarian parties were only occasionally included in governments. In 2017 authoritarian populists wield power in one third of Europe’s governments. This is an exceptional development over a short timespan.

5. Authoritarian populism has become the third ideological authority.

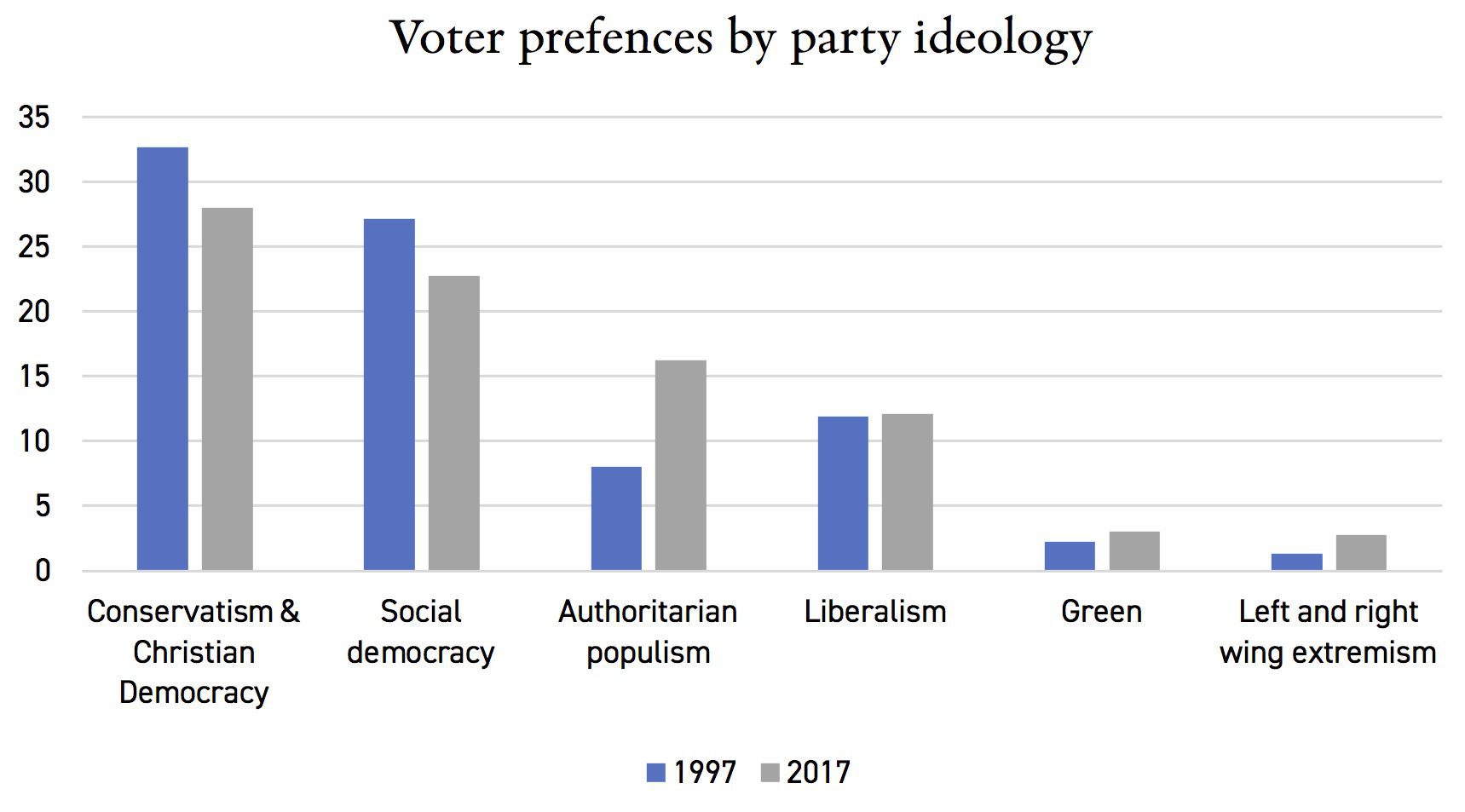

Authoritarian populism is a neophyte in European democracies. It is, however, well-liked. Today authoritarian populism constitute, in terms of voter support, the third ideological authority in European politics. Conservative and Christian Democrat parties gather on average roughly 27 percent in European elections, while Social Democrats amass about 23 percent. These continue to be the two dominant blocs, although both have had a negative trend during the last twenty years, dropping approximately five percentage units.

Liberal parties—for a long time the obvious third ideological power—gather a full eleven percent, and are thus comfortably surpassed by authoritarian populist parties with their fifteen percent. Accumulated support for extreme parties on left and right is generally the same as the total support for Green parties.

Fig. 10: European voters according to the different parties’ chief ideological labels.

The long-term trend is very clear. Authoritarian populism is growing faster than any other ideology. These parties guzzle voter shares from both Social Democracy and Conservatism. In the last twenty years the gap between, one the one hand, authoritarian populism and, on the other, Social Democracy and Conservatives, has shrunk with more than a half.

Conclusions

During the spring of 2017 a form of wishful thinking on populism took hold of many pundits and commentators. The idea of “peak populism” has become a mantra for those who interpret setbacks for Wilders and Le Pen as a sign that the seemingly inevitable success for populism now has reached its peak. Another popular idea has been “the Trump effect”, according to which European voters have been dismayed by president Trump’s first months in office to the extent that they now turn their backs on European parties that look like or are influenced by Trump.

None of these hypotheses receive any evident support if measured against the total development over the last few years. Voter support for populist parties remain at a very high level with very small changes compared to previous years.

It is true, however, that populist parties haven’t made gains to the extent that often was predicted. The most likely explanation for this is that general support for primarily populist parties grew dramatically during the winter of 2015-16 as a direct consequence of the European refugee crisis. A year later this effect seems to have subsided.

Populism has never before been a dominating ideological power in any European democracy. Today populist parties have a stronghold in both Poland and Hungary as well as in Greece. In France’ presidential election, populists in total received more votes than Emmanuel Macron. According to polls, Beppe Grillo’s Five Star Movement is consistently the biggest party in Italy, and Sverigedemokraterna is the second biggest party in Sweden according to almost every polling institute. If it is true that populism has peaked then it is also true that it has done so at an embarrassingly high level.

Literature

Abedi, Amir (2004), Anti-Political Establishement Parties: A Comparative Analysis. Routledge.

Barr, Robert R (2009), “Populists, outsiders and anti-establishment politics”. Party Politics 15.

Canovan, Margret (1999), “Trust the people! Populism and the Two Faces of Democracy”. Political Studies 47.

Gellner, Ernest & Ghita Ionescu (1969), Populism. It’s Meanings and national characteristics. New York: MacMillan.

Goodwin, Matthew (2011), “Right response. Understanding and countering populist extremism in Europe”. Chatham House.

Lerulf, Philip & Jan Å Johansson (2012), Extrema Europa. Nationalchauvinismens framväxt i Ungern, Nederländerna och Danmark. Lund: Sekel bokförlag.

Mudde, Cas (2007), Populist Radical Right Parties in Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Mudde, Cas (2010), The Populist Radical Right: A Pathological Normalcy”. West European Politics 33:6.

Pappas, Takis S (2016), “Modern populism: Research advances, conceptual and methodological pitfall, and the minimum definition”. Oxford Research Encyclop http://politics.oxfordre.com/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.001.0001/acrefore-9780190228637-e-17?rskey=A55nhK&result=53aedias.

Pelinka, Anton (2013), ”Right-wing populism: Concept and typology” in Right-wing populism in Europe. Politics and Discourse (Wodar, KhosraviNik &Mral, eds). London: Bloomsbury.

Zaslove, Andrej (2008), “Here to stay? Populism as a new party type”. European Review, 16:3.